Sunday Times 2

Unsettled still

P. PASPATHI, a 68-year-old former rubber tapper, recalled his journey from Sri Lanka in 1972 as if it happened yesterday. “First, we came to Ratnapura from the Peenkande estate. The city of gems, as Ratnapura means, was surrounded by plantations where many Indian Tamils worked. From there, we took a bus to Colombo before taking a train to Talaimannar and then hopped across the Palk Strait to reach Rameswaram, from where we were taken to the Mandapam camp. After a few days, we were sent to Puttur [in Dakshina Kannada district]. This was to be our new home although we were strangers here and missed our life in Sri Lanka,” he said. A gaunt man, Paspathi has a sharp, piercing gaze and thick bushy eyebrows, which he noticeably raises while making a point. While there are no glaring errors in his Kannada, it is not flawless, and his strong Tamil accent gives him away as someone who learnt the language late in his life.

A repatriate working as a rubber tapper at a KFDC plantation in Dakshina Kannada district

Paspathi was one among the few thousand Tamils of Indian origin who were repatriated from Sri Lankan plantations to Karnataka between 1972 and 1974. During this period, 988 families of “Plantation Tamils” were resettled in rubber plantations in Puttur and Sullia taluks of Dakshina Kannada district in coastal Karnataka. The original repatriates, along with their descendants, continue to live in the region, working for rubber plantations of the Karnataka Forest Development Corporation (KFDC). They face several problems, of which one is that of identity. This is manifest most strongly in questions of caste. The repatriates face other social and economic deprivations because of their unique historical legacy.

Early days

Paspathi did not know the exact story of how the Tamils of Indian origin had migrated to Sri Lanka, but he recalled his early days in Kowdichar Repatriates Colony in Puttur taluk, as he sat a few hundred metres away from the rubber plantation where he worked from 1972 to 2003. “We were like strangers here. We did not know the language, and it took us a few years before we settled down properly.” He does not know why he, along with a few other thousands, was chosen to be sent to Karnataka, but the small community of Tamil labourers made this their home. They were Indian citizens and they had come home-strange and new as it was.

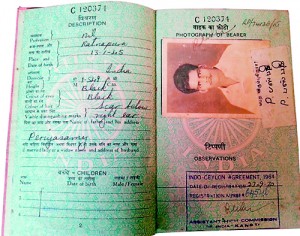

Many of the older plantation workers possess their birth certificates and passports issued in Sri Lanka. These documents are the first building blocks of a precious identity. Sirishunathan’s birth certificate states that he was born on March 29, 1945, to Muthusamy and Letchimy who were “Indian Tamil”, in Orwell Estate in Kandy district. Rasalechimie produced her repatriation passport issued at Kandy on June 2, 1971, by the Assistant High Commission of India, which states: “This passport is valid only for direct travel between India and Ceylon and may not be used for travel to any other country.” Under “National Status”, it clearly states that the bearer is a

P. Paspathi, now 68, made a home at Kowdichar Repatriates Colony

citizen of India. The journey of the passport-holder can be traced from this valuable document, and this particular woman was resettled in the Sullia Rubber Division on February 12, 1972, with her arrival attested by the Divisional Forest Officer of the Sullia Rubber Division.

Caste certificates

The repatriates possess voter identity cards, birth certificates and “above poverty line” (APL) ration cards, which provide them with three litres of cooking oil. Thus, their Indian citizenship is not contested, but they have been refused caste certificates over the past decade. Satish Kumar, president, Dakshina Kannada District Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribe Tamil Speakers’ Rights Organisation, says that there is enough official documentation to show that the repatriates from Sri Lanka should be treated as residents of Karnataka and granted caste certificates if they belong to the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes. A letter from the Social Welfare and Labour Department of the Government of Karnataka (dated April 8, 1991) that he produced said as much, adding that even refugees from Bangladesh who were rehabilitated in Karnataka during the Bangladesh liberation war should also be issued caste certificates. Letters from the Commissionerate of Rehabilitation, Chennai, and the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (FFR Division-Rehabilitation Wing) have also instructed the district administration to issue the necessary caste certificates.

According to K. Daivakumar, president, Dakhsina Kannada Schedule Caste/Schedule Tribe and Repatriates Welfare Association, almost 60 per cent of the repatriates belong to S.C. communities. The five major castes to which the S.C. members belong are the Pallan, Paraiyan (Paraya), Arunthathiyar, Chakkiliyan and Adi Dravida, which are recognised in Karnataka.

Strangely, the Dalits among the repatriates had caste certificates until the 1990s, but these have not been renewed in the past decade.

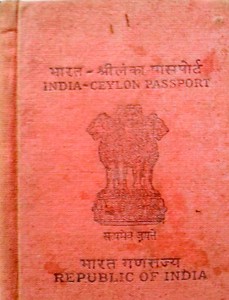

The cover of an India-Ceylon passport issued to one of the repatriates

S. Subrahmaniam of Darkasthu Repatriates Colony, for instance, displayed his caste certificate issued in 1993 which clearly identifies him as belonging to the Paraya caste, but he has not been able to renew this certificate. Rajaratnam from Otekaje Repatriates Colony in Sullia taluk displayed two caste certificates: his own, which says that he is an Adi Dravida, and his daughter’s, which recognises her as a Baira. Such strange anomalies can also be found among repatriates’ identities. (According to a notification issued by the Government of Karnataka, caste certificates issued from 2012 onwards need not be renewed, but that does not help the case of the repatriates.)

The reason given to deny caste certificates to the repatriates is based on a 1994 Supreme Court judgment that states that migrants from other States cannot be issued caste certificates (State of Maharashtra versus Union of India-1994 (4) SLR 494). Repatriate groups contest this and point to another judgment delivered by the Karnataka High Court which interpreted the apex court judgement as not applying to children of migrants from other States born in Karnataka [(Writ Petition No. 24690/ 2011 (GM-CC)].

The first page of P. Paspathi's passport showing his birthplace in Sri Lanka and his registration number as per the India-Sri Lanka pact of 1964

A few rejection notices received by the repatriates from the tehsildar’s office state that caste certificates are denied because they are “refugees”. The repatriates resent this categorisation strongly. “We are not refugees. We are repatriated Indian citizens,” says M. Muraleedhara, secretary, Dakhsina Kannada Schedule Caste/Schedule Tribe and Repatriates Welfare Association.

Clearly, these repatriates were settled in Karnataka directly upon their arrival in the country from Sri Lanka and they never spent time in any other State. It is not easy to see, therefore, how they can be considered migrants from other Indian States. The repatriates suspect manipulation by local Dalit leaders to deny them caste certificates, but this could not be independently confirmed by Frontline.

The issue was also raised in the Legislative Assembly last year. Govind M. Karjol, the Minister for Kannada and Culture in the previous Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government and a Dalit himself, strongly opposed the issuance of caste certificates to the repatriates and said they were migrants. A high-level committee headed by the Additional Chief Secretary was formed to look into the issue, but it has not made any recommendations yet.

There is also confusion with regard to the exact benefits guaranteed to the repatriates as per the 1964 and 1974 agreements. Daivakumar produced letters showing how the Commissionerate of Rehabilitation and Welfare of Non-Resident Tamils, Chennai, and the Assistant High Commission of India at Kandy in Sri Lanka have denied him any information in this regard; each directed him to approach the other’s office.

The KFDC provides permanent employment (Grade ‘D’ category) to two members from each family from among the original repatriates at a daily wage of Rs.215 (with some additional money based on output) on its rubber plantations that extend across 4,443 hectares. Each family that was originally repatriated was given a family card. Employment is provided on the basis of this card, and this is also linked to the provision of housing quarters. When the repatriates were initially settled here, they were not provided with permanent land or housing but were only provided jobs at the rubber plantations, which means that their right to the housing quarters is linked to their employment at the plantations on two generations. Members of the community find this unfair because two members from each family are forced to work for the KFDC as rubber tappers or as factory workers, however educated they are, to retain their quarters.

The restriction that the jobs and quarters would be given to only two generations of a family became contentious last year as eviction notices were sent to several repatriate families by the Assistant Commissioner of Labour, Mangalore Division, after two generations of their family members had retired.

D.R. Nataraj of Darkasthu Repatriates Colony in Puttur taluk was one among those who received eviction notices. He said: “We were shocked to receive the eviction notice but we refused to vacate our quarters and strongly protested this action by the KFDC. But the threat of eviction is constantly present even though my relatives, who belong to the third generation of my family, work on the rubber plantations.” This restrictive provision does not exist in the case of repatriates settled in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, according to information from the Commissionerate of Rehabilitation and Welfare of Non-Resident Tamils, Chennai.

Repatriate colonies

While the repatriates are settled in 43 colonies across Puttur and Sullia taluks, the total number of repatriates at present is unclear. Informal estimates from among the members of the community say that there are 25,000 to 30,000 of them. (This could not be independently verified by Frontline.) The colonies are deep in the midst of rubber plantations. They are well maintained but located at some distance from schools and hospitals. For instance, the Otekaje Repatriates colony in Sullia taluk, where 27 quarters are located, is five kilometres off the main road and can only be reached through a dirt track.

According to a news report, Sri Lankan repatriates in Araku Valley live like second-class citizens and have been denied state benefits (“Sri Lankan repatriates in Araku left to fend for themselves” by Ravi. P. Benjamin in The Hindu, May 25, 2012). Evidently, the problem that repatriates face is not restricted to Karnataka alone. Part of the problem is that the repatriates do not have a representative body across India. They have not managed to form one in Karnataka. Take the repatriates in Dakshina Kannada district, for example: the 1,800-odd workers are split between six labour unions, and there are also several caste-based organisations.

At Kowdichar Repatriates Colony, the rubber tappers are returning from a hard day’s labour. On hearing that a journalist has come inquiring about their caste certificates, many of them fetch documents. The older ones fetch their special passports issued in Sri Lanka while the middle-aged ones bring their lapsed caste certificates-two sets of documents, issued in different countries.

(Courtesy Frontline, India)