Columns

Why large trade deficits are a serious concern

View(s):Large trade deficits have been the dominating feature of the trade balance in the last three years. Once again this year’s external trade is heading towards a large deficit. With a trade deficit of as much as US$ 4.6 billion in the first half of the year we are heading towards a trade deficit of over US$ 9 billion. This is a serious concern.

Despite these large trade deficits, there has not been much concern about them owing to a high proportion of the deficit being offset by worker remittances, receipts from other services and capital inflows. This has resulted in complacency about the trade imbalance.

Why be concerned about the large trade deficit when most of it is offset by remittances, tourist earnings and other service receipts?

Trade deficits and remittances

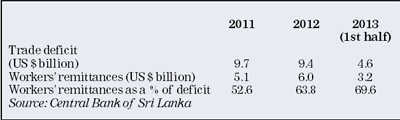

In 2011, despite a massive trade deficit of US$ 9.7 billion, the overall balance of payments deficit was only US$ 1.06 billion, mainly due to workers’ remittances offsetting 53 per cent of the trade deficit. Similarly, although the trade deficit was as much as US$ 9.4 billion in 2012, worker remittances of US$ 6.9 billion offset as much as 64 per cent of the trade deficit. Mainly due to this factor, the balance of payments registered an overall surplus of US$ 115 million last year.

In the first half of this year, the trade deficit was US$ 4.6 billion, while remittances amounted to as much as US$ 3.2 billion that offset as much as 70 per cent of the trade deficit. With enhanced tourist earnings expected this year, the overall balance of payments could be in surplus.

Therefore, it is argued that the largeness of the trade deficit is of no serious consequence to the balance of payments and the country’s reserve position. Then why are economists obsessed with the large trade deficit?

Export decline

The characteristic feature of the country’s exports for several years has been its declining trend both in terms of the proportion of exports to GDP and the country’s share of world exports. Furthermore, import expenditure has been nearly twice export earnings recently. For instance in 2011 and 2012, while exports were US$ 10.6 billion and US$ 9.8 billion, imports were US$ 20.3 billion and 19.2 billion, respectively. This demonstrates clearly the unhealthy export-import imbalance.

Implications

Exports are inadequate in the context of much larger import values and this imbalance strains the balance of trade and balance of payments. Quite apart from the impact of the trade deficit on the balance of payments, there are vital adverse repercussions of the export decline on the economy.

The decline in exports is an indicator that the country’s exports are becoming less competitive. This is especially so for manufactured exports which displayed a healthy growth since liberalisation of the economy in 1977. The trend in export decline has continued into this year and according to the Central Bank, exports declined by a further 4.5 per cent in the first half of this year.

The setback to exports is partly a reflection of the slow growth of the global economy. The near recessionary condition in the United States and European countries — the main markets for Sri Lanka’s manufactured exports, such as garments, rubber products, leather goods, ceramics and other manufactures — is no doubt a big blow. In addition, the withdrawal of the GSP+ concession by European Union countries has also hit our manufactured exports. As a result, we cannot compete with other Asian countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal and Vietnam that enjoy the GSP+ tariff concessions.

Some comparator countries have been successful in increasing their export share in world trade despite the decline in demand from industrial countries. This means that those countries have become more competitive relative to Sri Lanka or have maintained their competitiveness while Sri Lanka’s competitiveness has declined. That is why the country is exporting less and importing more.

The decline in competitiveness of manufactured exports in particular is problematical because Sri Lanka exports goods that have a larger labour component compared to its imports which limits the growth of employment in manufacturing. Moreover, a country like Sri Lanka cannot rely on capital inflows to continue to maintain balance of payments viability because when remittances, tourist earnings and other service receipts decline, the country has to borrow more. This increases debt service costs that have to be ultimately repaid through increased export earnings.

Serious implications

The plain truth has been a reduction in exports with a decline in several manufactured exports. Many industries have stopped production or decreased their scale of production. The impacts of these on incomes and livelihoods are still not assessed. Reduced incomes, output growth and retrenchment of labour in a sector that holds more promise than continuing to rely on the current basket of exports is a threat to economic development. Therefore the export decline is not only a strain on the balance of payments but a serious setback to the country’s industrial development.

The serious implications of the decline in exports, particularly of manufactured exports, are that it is a setback to the country’s industrial development that is a pre-requisite for economic growth. The setback to exports is a factor in increasing unemployment and reducing incomes of workers. Therefore quite apart from the issue of the adverse trade balance, the trade deficit caused by a decline in exports is a threat to economic growth.

Remedial measures

If these implications are understood, policy makers would take remedial measures to redress the conditions that have resulted in an export decline. Among the remedial measures, it is important to address the macroeconomic factors that have restrained export growth. These are the increased pattern of growth in the non-tradable sectors mostly due to the faster growth of construction related to government expenditures, an appreciated exchange rate and higher prices of electricity, a vital input into the production of tradable goods.

The most important macroeconomic factor that leads to higher trade deficits is the higher aggregate demand growth due to the fiscal deficit. Could we remain complacent about this? The offsetting of the large trade deficits by workers’ remittances and tourism earnings is not a good reason to ignore the serious consequences of an export decline on the country’s economic growth.

comments powered by Disqus