News

CKD: The killer still at large despite worldwide hunt

SANDAMALGAMA, Sri Lanka – In this tiny Sri Lankan village, rice farmer Wimal Rajaratna sits cross-legged on a wooden bed, peering out toward lush palm trees that surround his home. Listless and weak, the 46-year old father of two anxiously awaits word on whether his body can accept a kidney donation that offers his only chance of survival.

In Uddanam, India, a reed-thin farmer named Laxmi Narayna prepares for the gruelling two-day journey he takes twice every week. For most of his 46 years, his job involved shimmying up palm trees to harvest coconuts at the top. He now spends most of his time negotiating the more than 100-mile bus trips he takes to receive the dialysis treatments that keep him alive.

Ten thousand miles away, in the Nicaraguan community of La Isla, Maudiel Martinez dreads returning to the rolling sugarcane fields where he spent most of his teenage years at work with a machete. Blood tests by the sugar company that employed him found that his kidneys were seriously damaged – and exertion beneath the tropical sun could tip the 20-year-old’s health into a lethal spiral.

A CKD victim. Pic by Anna Berry-Jester for the Centre for Public Integrity

In three countries on opposite ends of the world, these men face the same deadly mystery: their kidneys are failing, and no one knows why.

A mysterious form of chronic kidney disease – CKD – is afflicting thousands of people in rural, agricultural communities in Sri Lanka, India and Central America. The struggle to identify its causes is baffling researchers across multiple continents and posing a lethal puzzle worthy of Sherlock Holmes.

The three epidemics have crucial threads in common. The victims are relatively young and mostly farm workers, and few suffer from diabetes and high blood pressure, the usual risk factors for renal disease. They experience a rare form of kidney damage, known as tubulo-interstitial disease, consistent with severe dehydration and toxic poisoning.

Other common links offer clues to a possible cause. The epidemics affect sharply defined geographic areas that are stunningly fertile and swelteringly hot. The victims mostly conduct heavy manual labour, have little formal education and lack easy access to medical care. Pesticides are used heavily, and communities drink local groundwater. In each case, the disease began surging in the 1990s.

Despite a decade of research in each affected region — and a potentially noteworthy discovery this year in Sri Lanka — scientists have yet to prove a chemical at fault or means of exposure. Researchers are convinced that if they could identify the culprit, the outbreaks could be stopped and the death toll reversed.

“I absolutely think that it’s preventable,” said Daniel Brooks, an epidemiologist at Boston University who is leading a study in Nicaragua of the new form of CKD.

In a sense, researchers are waging a race against three parallel epidemics occurring across multiple continents. Yet the search for clues was slow to begin, with governments including the United States moving with little urgency despite warnings of the disease’s toll. And separate groups of researchers — each chasing clues to kidney epidemics across the globe — have not fully explored whether they are linked together.

More than 16,000 men died of kidney failure in Central America from 2005 to 2009, with annual deaths increasing more than threefold since 1990, according to an analysis of World Health Organization data. In Sri Lanka, the WHO says at least 8,000 people suffer from chronic kidney disease of unknown cause, though other sources put the number more than double that. In the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, more than 1,500 have been treated for the ailment since 2007.“There’s a need to connect all the dots between these different outbreaks,” said Dr. Ajay Singh, a nephrologist at Harvard Medical School who is leading a study of the epidemic in India.

Meantime, questions persist. Are tainted agrochemicals to blame? Dehydration in the fields aggravated by dangerous working conditions? Or, could multiple culprits exist, with different causes in each region?

From Sri Lanka to India to Central America, all the victims know is that something in their lush, hauntingly beautiful surroundings is wasting away their lives. In one patch of rural Nicaragua, so many men have died that the community is called the Island of the Widows. In the Indian region of Uddanam, a reverse trend has taken hold: Couples decline to marry at all.

In Sri Lanka, a suspect emerges

Wimal Rajaratna has worked in the rice paddies since he was 20. He enjoyed good health until December 2011, when he began suffering an alarming array of pains. His head pounded, his knees ached at the joints, and his appetite deserted him.

A visit to the doctor revealed that his levels of creatinine, a chemical in the blood that indicates kidney function, were an astronomical 9.45 mg/dL — more than seven times higher than normal.

Rajaratna’s illness is part of an epidemic sweeping northern Sri Lanka. The disease affects three provinces in the north central region of the country, and prevalence in the affected region is 15 percent, according to a study by the Sri Lankan Health Ministry and WHO.

The Government has even come up with a name for it: CKDu, chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology.

Since 2009, the Health Ministry and WHO have embarked on the world’s largest and most comprehensive study of CKDu. They have sampled patients’ blood and urine, tested the soil, water and food, and surveyed and mapped the population. “We need to do full-blown research on this and then find out the causative agents,” said Dr. Palitha Mahipala, the Health Ministry’s additional secretary who heads the official study.

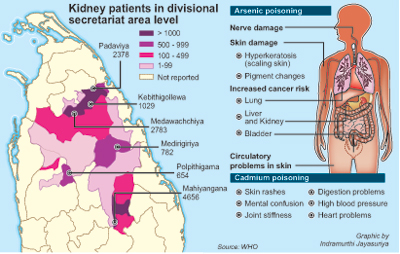

Finally, in June 2012, the Health Ministry and WHO publicly identified chemicals they said were an essential cause of the disease. The culprits: The heavy metals cadmium and arsenic, through low-level exposure likely occurring through the food chain.

Cadmium is often present in phosphate-based fertilizers, while arsenic has been detected in several Sri Lankan pesticides and also occurs naturally in some parts of South Asia.

The official findings in Sri Lanka represent a potential breakthrough. But the scientific programme has not yet released any of its data behind its findings – leaving lingering doubts about its conclusions.In sufficient quantities, cadmium and arsenic cause the same rare type of kidney damage found in the disease’s victims. However, researchers said most of their patients’ tests and environmental samples showed these chemicals at levels below the exposure limits set by United Nations agencies.

Mahipala acknowledged that “we can’t really come to a conclusion” about the effects of specific exposures that remain within international limits.

The WHO says it will release official study results in late October that will include hard data.

In India, the trouble in Uddanam

Laxmi Narayna’s village, Gonaputtuga, is part of a verdant rural belt along India’s eastern coast called Uddanam. Spanning less than 100 miles, this stretch of villages near the northern border of the Andhra Pradesh state has been suffering for two decades from a mysterious strain of CKD.

Healthy throughout his 46 years, Narayna began experiencing a painful series of ailments in late 2011. His body began to swell, he had difficulty urinating and he found blood in his stool. Unable to work after decades spent harvesting coconuts from the top of palm trees, Narayna spends his days resting and traveling back and forth from dialysis. “Now, I do nothing,” he said.

India’s wave of CKD is smaller than the other outbreaks – but highly concentrated. Unpublished results from a study by Harvard Medical School found that 37% of the population in the hardest hit village, Akkupalli, had the disease. From 2007 to 2012, 1,520 patients from Uddanam received care for CKD from a state health insurance program for the poor. But this number significantly understates the burden of a disease that is latent until it reaches its advanced, deadly stages.

Unlike Sri Lanka and Central America, the illness affects men and women roughly equally, according to separate findings by researchers from Harvard and Stony Brook University. The gender equality and geographic concentration of the illness have focused concentration on potential contamination, particularly in the drinking water.

For Laxmi Narayna, time is running out. At the Seven Hills Hospital, he smiles bravely and says he feels no pain, but his thin frame is dwarfed by the wide cot he rests on.

In Central America, the science of sweat

Maudiel Martinez started working in the cane fields at 14. His father had died of CKD two years before, and his family was struggling. After three years of work at the Ingenio San Antonio plantation, he was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease at 17. The epidemic in Central America spans six countries along a nearly 700-mile stretch of the Pacific coast. Roughly 3,000 men in the region die of kidney failure each year, and the disease has killed more men in El Salvador and Nicaragua than diabetes, HIV/AIDS and leukemia combined in the last five years on record, The Center for Public Integrity found.

The BU team has pinpointed evidence suggesting that heat stress and dehydration are key contributing factors. Yet recent tests of adolescents found that many had markers of kidney damage without ever having entered the fields – suggesting a pre-existing exposure as well.

Workers like Martinez continue to place themselves at risk to support their families. At 20 years old, he is recently married, with his wife expecting a baby. “I feel like every day I work I’m taking away a little part of my life,” Martinez said.

(The Centre for Public Integrity is a non-profit independent investigative news outlet in Washington DC.

To read more of its stories on this topic, go to publicintegrity.org.)

Hard water linked to CKDu: Rajarata scientists

By Hansani Bandara

The controversy over the arsenic content in fertilizer has come to the centre-stage again — with Rajarata University researchers claiming that hard water is responsible for the high prevalence of the Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown aetiology or origin (CKDu) in the North Central Province and the Uva.

By the end of 2011, the number of CKDu cases reported from the NCP and Uva was 15,851. The researchers claimed that the situation was so serious that today some 15 per cent of the NCP population in the age group 15-70 was either suffering from the disease or in the early stages of it.

The JHU held a news conference to express its disappointment at the government’s inaction towards the arsenic content in agrochemicals.Pic by Kithsiri De Mel

The latest report released by the World Health Organisation states that the increase in the number of patients is due to long term exposure of several risk factors toxic to the kidney. They include cadmium and arsenic.Rajarata University Pharmacology lecturer M. A. C. S. Jayasumana, who together with other academics conducted a research on the presence of arsenic in pesticides used in the country, said that when examining the autopsy reports of CKDu patients, kidney toxic substances such as cadmium arsenate and arsenic were found in kidney tissues.

He attributed the high prevalence of the disease in these NCP and the Uva to the presence of a high arsenic content in natural water resources. Ground water gets contaminated due to the usage of fertilizer containing arsenic, he said.

Dr. Jayasumana said their research showed there was a positive relationship between the increased number of CKDu patients and the hardness of the ground water.

(The hardness of the water is determined by the amount of minerals in the water)The higher the ground water hardness in a particular area is, the more the number of patients from there. Since the ground water hardness in these areas is in the high range of 400 to 100 mg/litre, the Rajarata University research concluded that arsenic entered the human body through hard water, causing the CKDu.

Dr. Jayasumana said people who consume rice produced by using arsenic-rich fertilizer also face the health hazard. If arsenic enters the body through food, it could harm the liver and also cause cancer and diabetes.

As the crisis deepens, the Jathika Hela Urumaya parliamentarian on Tuesday staged a demonstration to draw the people’s attention to the issue.

“It is distressing to say that the authorities have not taken any measures to stop the distribution of low quality fertilizer and none of the recommendations of the WHO report has been implemented. The officials have sold themselves to the few companies that import fertilizers and are reluctant to take action against them,” said JHU parliamentarian Ven. Athuraliye Rathana Thera.

The money spent on fertilizer subsidy — some Rs. 55 billion — should be given to farmers, he said adding that he believed that the high number of CKDu cases in the country was due to the use of arsenic-laden low quality fertilizer.

The Thera said the concept of sustainable agriculture should be promoted island-wide and farmers must be encouraged to cultivate without using chemical fertilizer.

He vowed to continue the protest campaign until the government stopped the import of low quality fertilizer.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus