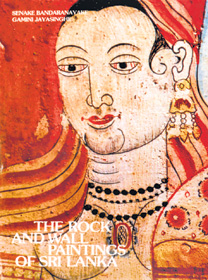

A solid work in range and richnessThe Rock and Wall Paintings of Sri Lanka. A Stamford Lake Facsimile Edition. Afterword by the author. Reviewed by Prof. Ashley Halpé. The first comprehensive work in this field, Rock and Wall Paintings treats its material with authority and panache to achieve the status of a definitive volume. Earlier, students and readers had to forage through monographs, JRAS and obscure articles in defunct journals, while the few books of broader scope like Paranavitana’s Art of the Ancient Sinhalese or his UNESCO volume and Dhanapala’s Buddhist Paintings from Shrines and Temples in Ceylon were tantalizingly suggestive rather than exhaustive. Siri Gunasinghe’s Buddhist Paintings concentrated on the Kandy period while Manjusri’s Design Elements from Sri Lankan Temple Paintings was also highly specialized. General readers can have had little conception of the range and richness of the pictorial tradition now made accessible to them by Senaka Bandaranayake’s meticulous and searchingly analytical exposition and Gamini Jayasinghe’s brilliant photography. The book necessarily concentrates on the Historical period which is studied in its early, middle and late phases, but the art of pre-history is not neglected. The first, introductory, chapter which describes the evolution of a pictorial tradition includes a well-judged outline of the prehistoric period identifying the principal sources of information, defining the three basic types of rock art monochrome silhouette, polychrome paintings and and incised representations and describing the techniques and concepts involved. Professor Bandaranayake notes the considerable degree of uncertainty regarding the data and authorship of these paintings since none of the examples has been recovered from excavated or stratigraphically related contexts nor dated by any objective method. Hence some of these paintings of ‘prehistoric type’ may even be nearly contemporary graffiti’ inscribed by Veddahs or other forest dwellers, or productions of historical rather than prehistoric times. However their ‘authenticity as an organic rock-shelter art’ is not in doubt so that, as Professor Bandaranayake suggests, “it provides a bright if elusive image of the imaginative world of prehistoric man even though ancient man’s use of colour for decorating ritual or imaginative expression will remain virtually unknown since pigment is one of the ‘most fragile of artifacts’.”

Prof. Bandaranayake makes a fascinating cross-reference to brand marks on cattle, the design and colouring of ritual masks and the ornamentation of grain-storage bins (bihi citra) which often bear unmistakable echoes of the style and imagery of the primitive rock shelter paintings reminding us of the possibility of deep-seated archetypal patterns, persisting from that grey time to this. The first chapter concludes its overview of the tradition with the transitional work of Sarlis and the contemporary phase which begins with Solias Mendis’s vigorous adaptation of the Bengali style and arrives with George Keyt’s murals at the Gotami Vihara and Albert Dharmasiri’s at Veheragodella at contemporary interpretations of traditional subjects. (In the last paragraph of the book Prof. Bandaranayake goes back to this point, amplifying it by referring to the work of the ‘surrealist’ master of the hell scenes at Botale… or the vigorous but recherché romanticism of Solias Mendis or George Keyt which are as much a comment on our perceptions of that tradition and the historical trajectory that produced it as they are indicators and reflectors of our contemporary moment). The chapter includes a valuable discussion of context and method bringing out, for instance, the special importance of image-houses and the basic principles by which the painting of the various areas of an image-house are governed, going beyond decoration to the ‘symbolic recreation’ of ‘ a kind of cosmic geography’. The wall-paintings transform the architectural interior into an ‘otherworldly environment’, their organization leading the devotee through a didactic process and then inwards to a contemplative encounter with the ‘principal icon, a seated, standing or recumbent Buddha’. The organization of the wall space in the outer chamber into narrative registers is similarly deliberate, making ‘effective use of the fourth dimension, time’ to lead the observer through episodes of the suvisi vivarana, or the Jataka stories or other stories from Buddhist literature. The presentation of a narrative is ‘essentially theatrical or cinematic’ – or, in fact, closest to the method of the modern comic strip, though one might say it is superior to the latter in adopting a zig-zag movement, like the arrangement of squares on a snakes-and-ladders board, which enables an ambulant observer to follow the sequence without interruption. The early and middle periods are documented and discussed very thoroughly, almost all the available material being incorporated. Prof. Bandaranayake notes that, unlike sculpture or architecture, painting ‘comes into view’ in a fully formed mode in the classic art of Sigiriya, but marshals evidence that the work at Sigiriya is clearly the product of a mature tradition of pictorial art with several centuries of development behind it, using evidence from literary sources as well as from the comparison with the evolution of sculpture from about the 2nd – 4th centuries A.D. onwards : ‘ in their finally evolved form they closely approximate to the classic style of the Sigiriya paintings’.The ‘patterns of development’ of middle-period art also suggest a preceding evolutionary history similar to that of the sculpture. The commentary on the Sigiriya paintings is extensive and ably surveys the present state of knowledge while commenting critically on discoveries made and views expressed at various times during the one hundred years of modern encounters with Sigiriya. The discussion of the Boulder Garden paintings is very welcome both with reference to and the importance of these paintings – though many are vestigial – as evidence of the ‘continuation of the Sigiriya school’ until perhaps as late as the 12th or 13th century – and in terms of specifices. Thus Professor Bandaranayake draws attention, for example, to the masterpiece of expressionist painting, displaying considerable imaginative range and artistic virtuosity in the remains of ceiling paintings in the shelter known as the ‘Cobra-hood Cave’. Suitable attention is paid to the cave-shrines of the Anuradhapura period and to the remarkable work at Hindagala (now largely destroyed) – ‘one of the most significant pictorial remains of the Middle Historical era’ with features not seen in the Sigiriya paintings – for example, the unusual psychological dimensions noticed by Siri Gunasinghe – making it ‘certainly the most complex statement’ of early Sri Lankan painting. The late 13th c. work at Polonnaruwa, as of the panel from the south wall of the entrance of the Tivanka image house is seen as marking the end of the Middle Historical era and of the cultural epoch which began with the Sigiriya period. A study of the paintings of the latter part of the epoch has to focus on the murals at the ‘unique’ Tivanka image-house, the ‘sole surviving example’ of a building of the period that ‘retains at least some element of its wall paintings in their original form’. Prof. Bandaranayake indicates that the Tivamka murals ‘throw light on many aspects of the Sri Lankan tradition – such as the planning and organization of painted wall space, the selection of themes, compositional techniques, the treatment of the human figure as well as chronology and stylistic variation’. With regard to the last two points he identifies more than one phase of painterly activity, tentatively suggesting three phases which are stylistically distinct – late classic, sub classic and post-classic. He draws attention to the “highly elegant, elaborate and ‘courtly’ manner of the inner murals and the ‘much sketchier and illustrational’ outer murals, painted ‘more loosely’. The Culla Paduma Jataka sequence on the south wall of the vestibule displays a sureness and precision of line, and compositional complexity, while the wagon and wagon-driver representation from the Temiya Jataka is in “a much stiffer and stylized ‘folk’ style.” And where he inferred a pre-5th c. phase of development of the Sri Lankan tradition from the developments he had noted in sculpture and architecture (backed by literary evidence) in the illustrational and narrative mode of the later Tivamka murals he notes an anticipation of the style and technique of the wall paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries. While the latter we arrive at the Late Historical Period – in some ways the most fascinating part of the exercise, if the least rewarding in terms of aesthetic and numinous experience. The murals spread over more than 300 temples in the central and Southern areas make up in their profusion and variety for what they lack of the grace of Sigiriya or the dignity of Tivanka, though they also display the bustling vitality of an active tradition. Professor Bandaranayake comments on a few selected locations, supported by Gamini Jayasinghe’s photographs, to illustrate the range of material and bring out the issues involved. He calls in question the earlier simplification that the high art of the Early and Middle Historical periods yielded place to the work of folk craftsmen of Kandy and the South in the Late period, pointing to its highly complex and schematic organization of painted space and its abstract use of colour’ and to N.B.M. Seneviratne’s view that they are sophisticated. Seneviratne argues that it might be possible to show that the medieval art idiom had really been responsive to a number of cultural changes and was thus in important essentials perfectly dynamic and expressive of each of these changes, rather than that it exemplifies Coomaraswamy’s view that ‘by the eighteenth century Sinhalese art had become a provincial and practically a folk art’, vigorous but expressing the ‘uncomplicated attitude of a simple people’. The presentation of the pictorial material does justice to the complexity of the issues providing plentiful evidence, for example, that might support either of the above views. The Byzantine stylization and hieratic poise of the figures in Plate 148 face the unsophisticated earthiness and the disjunctive use of space in the Patacara episode in Plate 144 and both are from difficult parts of the same temple (Kataluva). The exquisite designs and colour symphonies of Karagampitiya’s ceilings look down on pure Victorian kitsch in some of the representational panels. Professor Bandaranayake opens up fruitful lines for speculation without trying to suggest that he has all the answers. Thus he demonstrates the interaction of Kandyan and Southern stylistic tendencies without adopting the simpler view of a centripetal diffusion and adulteration. He also lays to rest the theory of a ‘break’ between the Polonnaruva period and the 18th c, tracing lines of continuity through the Gampola period, the painted beards of a 13th/14c ola manuscript now in the British Library, the Gadaladeniya and Alavatura temples, the Aludeniya door-frame (‘post-classic art’ anticipating ‘the elegance and complexity of the figural representation in the Kotte period ivories, which are nearly two centuries later’) and Heydt’s early 18th c drawing of Mulkirigala. In these and many other cases Professor Bandaranayake shows a comprehensive grasp of earlier scholarship and easy familiarity with the material now available while contributing ably to our reperception of the many issues raised by the study of a specific period or of the tradition as a whole. There is suitable reference to the functional contexts in which the rock and wall paintings occur as well as to the broader South Asian matrix. In relation to the latter he makes the important general observation that in regional perspective, the Sri Lankan murals take their place in a broad spectrum of South and Southeast/Asian traditions while also having their own specific characteristics and continuities. Gamini Jayasinghe’s contribution is central. There is true creative flair in his use of light and filters, imparting subtle drama to his views and perspectives, missing nothing where precision of detail is of the essence, and being unfailingly interesting without being arty in his choice of angle. With 169 such colour photographs, excellently reproduced and several black and white ones, the book affords readers an exciting visual encounter with an entire pictorial tradition. The visual material includes several useful maps, well-conceived charts and diagrams, and some admirably clear and elegant line-drawings. The book is very satisfactorily indexed and a list of illustrations provided. The Bibliography, though described as ‘select’ is in fact, substantial and includes useful material on other South and Southeast Asian traditions. The Notes convey much useful supplementary information, comment and cross-reference. The total impact richly repays designer Albert Dharmasiri and the author for the ‘long evenings’ spent in discussing and designing the book. Linking the skills of the scholar, the photographer, the writer and designer, The Rock and Wall Painting of Sri Lanka is as brilliant and beautiful in conception as in execution. (The reviewer is Emeritus Professor of English, University of Peradeniya) The launch

"Arts and crafts are part of the identity of a civilization" said Prof. Nimal de Silva, highlighting the significance of the launching of the facsimile edition of Prof. Senaka Bandaranayake's book, 'Rock and Wall Paintings of Sri Lanka'. The book which was originally published in 1986 fast became a textbook for scholars, and the nomenclature that was introduced in the book has now become standard, he added. Prof. Silva was speaking at the ceremony held on April 29 at the Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology (PGIAR). The event was well attended by lovers of Sri Lankan art and scholars. Dr. Roland Silva, long-time colleague and close friend of Prof. Bandaranayake, in his remarks commended Prof. Bandaranayake on his work to re-integrate the segments of history of Sri Lankan paintings. The book is published by Stamford Lake (Pvt) Ltd, and the company's CEO presented the first copies to Prof. Bandaranayake, and the panel of guest speakers at the event - Dr. Roland Silva, Prof. Nimal de Silva, Mr. Sirinimal Lakdusinghe, and Mr. Rathnasiri Arangala. |

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |