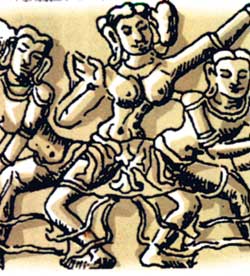

Music makers, actors and dancing maidens of yore"Young girls dressed as Sigiriya damsels performed at the residence of the Speaker…scantily clad young women in the presence of monks" (Photo caption "S/ Times 3/2") The prim disapproval implicit in this account took my mind back to the exquisitely carved dancing girls in Yapahuva’s Dalada Maligawa , Vilgam Vihara, Gadaladeniya and many other ancient temples which portray the vital role that song and dance played in Buddhist festivals of ancient Lanka. Wonderful traditions now almost erased from popular memory after the fell hand of the missionaries of 1505 abolished these "pagan rites". The caption writer’s ill-informed disapproval is a puritanical hangover of this colonial mindset. Festivals in the Mahavansa The Mahavansa is rich with descriptions of song and dance in Lanka’s royal courts. It records that Pandukabhaya [437-367 B.C], the great unifier of pre-Buddhist Lanka, presided over "royal command performances" of dance and music. Devanampiyatissa [307-267B.C] rode his State elephant in procession to Mahamegha Park attended by dancers and musicians. The reign of great Dutthagamani [161-137 B.C] abounds with description of the role that the lively arts played on ceremonial occasions. After his great victory the king held a grand investiture on the terrace of his palace, for his leading general Phussadeva "attended by dancers and ministers" (an intriguing combination!).

The king ceremonially commenced work on the Mahathupa (Ruvanweliseya) surrounded by musicians and richly clad dancers. When their great patron King Dutthagamani passed away, after a reign of 24 years, women dancers attended his funeral and, as a gesture of mourning, laid off their ornaments at the spot later known as Mukutamuttasala. The pious king Bhatikabhaya [20 B.C-9A.C] "caused to be performed in honour of theMahathupa divers mimic dances and concerts to the accompaniment of …all kinds of musical instruments”. His successor Mahadathika Mahanaga [9-21A.C] commanded a festival at the foot of Mihintale mountain at which mimic dances, song and music were played. It is interesting to speculate what these "mimic dances" were. It is most likely that these were dramas set to music with players acting [mimicking] various characters to dance and music, as in Sarachchandra’s Maname many centuries later. Alas, we will never know. Celebrations in the Culavamsa Parakramabahu the Great [1153-1186A.C] has been a truly amazing hero and scholar. He won sovereignty over Sri Lanka after winning a series of battles by force of arms and shrewd diplomacy. Thoroughly schooled in traditional Buddhist learning he had exercised the royal privilege to cleanse and reform the Sangha which had declined in the earlier war-torn years. He is described as a master of the rasas [muses]. During a lull in the battle with Manabarana he rested and "hearkened to the singing of various songstresses". He enshrined the Buddha’s Bowl Relic in a grand pavilion surrounded with other pavilions housing splendidly attired dancing girls accompanied by musicians with lutes, drums and the like, and by bands of female musicians to honour the Sacred Relic with dance, song and music. Parakramabahu was a master of many arts including that of dance and song. He even established a centre in the palace precincts to train "sons of the soil" in various arts including song and dance. After victory n Malayarata he is reported to have "dwelt in ease and spent the time sportively witnessing performances of song and dance”. His consort Queen Rupavati was also "learned and skilful in dance and song". The chronicle also provides an intriguing footnote indicating that mimic dances and song were enjoyed by the common folk who were entertained by troupes of travelling musicians. During his many campaigns Parakramabahu used them as spies to infiltrate and report on his enemies. He sent them disguised as snake charmers, palmists, skilled in song and dance and some, most interestingly, "played with leather dolls". It is reasonable to presume that these ‘dolls’ were puppets used, even today, in traditional shadow plays in Java. Yet another long lost tradition. The Kalinga Forest Gal Asana inscription speaks of the Lion Seat from which King Nissanka Malla [1186-1197 A.C] witnessed artistic performances of dance and song in the Kalinga Park. The scholar king "Pandita" Parakramabahu II [1234-1269A.C] held many festivals, in honour of the Tooth and Bowl Relics, "ravishing by reason of the most exquisite dances and songs of dancers who on splendid stages ….performed while assuming different characters, divers dances and sang various songs. The noise of the festival was increased by the sound of the five musical instruments which produced the illusion of the roar of the great ocean". "Dancing girls performed delightful dances and sang songs" at the grand festivals held by Parakramabahu IV [1325/6 A.C] to honour the Tooth and Bowl Relics. The reign of Parakramabahu VI of Kotte [1412-1467 A.C.] saw the last fine flowering of Sinhala music, dance and poetry. The king not only was a connoisseur of the lively arts but he actively encouraged them by founding educational establishments of repute to impart instruction in the arts and sciences. Four brief decades later this flowering wilted and died with the Portuguese incursion and their enthronement of their puppet the Catholic Don Juan Dharmapala. No longer were the Sacred Relics safe, nor would they ever be honoured in royal festivals of song and dance. The Sandesa Poems The Sandesa poems are a rich , and florid, mine of information of music, song and dance. The 14th century Tisara Sandesa evokes the sensuous enchantment of the dancers: With the sound of the hornet flew the music of the flute Decline and revival

The decline and fall of Sinhala monarchy with its intimate relations with the Sacred Relics and attendant rituals inevitably led to the withering away of dance and music as refined entertainment, and the passing away of traditional artistes, in the absence of royal patronage. The barest minimum of dance and music essential for the rituals of the Dalada Maligawa and other Kandyan temples survived thanks to the solemn undertaking the Chieftains wrested from the British "to protect the religion of the Boodhoo". So did the coarse bucolic humour of folk plays as ‘Sokori’ where men played women’s roles. The Maritime Provinces had lost a royal court a few centuries earlier. As a result the only song and dance that survived did so thanks to the primordial shamanistic rituals of ‘Bali’ and ‘Thovil’. This gloomy scenario began to dissolve with the quiet surge of Sinhala pride in the early decades of the last century. John de Silva’s stirring songs in his plays based on Sri Lanka’s history were the inspiration for a way forward in Sinhala music. A giant leap, literally, was made in the early 1930s by Miriam Peiris [daughter of the historian Sir Paul and mother of the cellist Rohan de Saram]. She persuaded a traditional ‘gurunnanse’to teach her the ‘Ves Netuma’ and defied tradition by becoming the first woman dancer, in centuries, to don its full panoply and dance before an astounded public. She scored yet another first in performing this dance before the cameras of Alexander Korda’s film "The Drum". Then it was the great Chitrasena who raised Kandyan dance to a refined art and choreographed modern ballets based on its movements and rhythms. His other revolution was the introduction of a corps de ballet of women. This example was enthusiastically taken up by government training colleges, who went on to produce the many dancing teachers now staffing almost every school and producing troupes of school children for various public displays.(Nowadays they seem to be fighting a losing battle against school marching bands in comic Ruritanian uniforms) I recall another almost unknown woman dancer from a traditional dancer clan, Ransina of Hanguranketa whose persistence enabled her to establish her own ‘Kalayatana’ on a bare hilltop in 1957. She was a pioneer entrepreneur of dance whose achievement has never earned her the recognition she so richly deserves. Former Diyawadana Nilame, the history scholar Nissanka Wijeyaratne deserves to be honoured for reintroducing a tradition, dormant for many centuries, of women dancers in the magnificent Dalada Esala Perahera. These small steps for womankind are not only the way forward but also anchored solid in centuries old traditions when women sang and danced to honour the Sacred Relics. [I am indebted to Dr.Nandasena Mudiyanse’s article in The Buddhist Vol.XLIV No.2] |

||||||

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and the source. |

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |