The wild flower meadows of KyrgyzstanFrom Khiva to Issy-Kul : An Islamic Journey in the Central Asian Heartlands of Timur (Part 4) While much of Timur's architectural heritage (as the previous articles revealed) lay principally in modern Uzbekistan, less explored attractions dot the steppes and mountains of adjoining Kyrgyzstan. It was, in 1999, a lesser known area, having gained independence from the Soviet Union only in 1991. Despite efforts to ascertain facilities for independent travel in Kyrgyzstan, it was evident that the isolated terrain did not suit casual meanderings by public transport. Uncharacteristically, a local was requested to meet us, a travelling companion and myself, at a borderpoint between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan and drive us in a local jeep through this rugged country. Driven Nowhere by "Borat" With this arrangement, I left Tashkent one Spring morning having recruited a Maruti sized minivan (microvan is more apt), driven by a tall lanky moustached local, years ahead but physically and in mannerism a direct forerunner to "Borat of Kazakhstan" film- fame. His smart dark suit, polished black shoes and suave swagger were stylish; his English was limited and our conversations thereby comically aimless. Our route took us eastwards to a particular border-crossing ostensibly known to him - but not indicated on any map. The road through the mountainous Kamchick Pass was severely pot-holed; tackling this in a microvan with wheels almost the size of baby-prams' was a strain but my driver was cheerful and the radio was loud. With his head touching the ceiling, it was a wonder that the van's roof did not acquire cartoon-styled bumps as we sped downhill. The Poppy Fields of Ferghana Valley From a narrow mountainous neck of north-central Uzbekistan, we descended to the famed Ferghana Valley, known as the pasturelands of Genghis Khan's magnificent Celestial horses as well as for rolling red poppyfields. Along the roads, green fields interlaced with yellow and white spring flowers presented an uncontained spectacle. The valley depression, ringed by mountains from Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, is also home to the orthodox Muslim stronghold of Kokand (10C AD), a historical counterpart to Silk Road settlements like Yarkand in Xinjiang. However, due to prevailing security tensions (there is additionally a long desire for a pan-Islamic alliance of -stans), I was regretfully forced to bypass this old Khanate.

Other problems, however, preoccupied me. Having meandered with mislaid conviction through endless rural roads on the valley floor, our driver was lost in a 22,000 sq km Ferghana Valley. A 2pm deadline to meet our Kyrgyz companion gnawed on me as I was very wary of being stranded in such isolated and security-sensitive surroundings. In a valley of this size, passing help was infrequent and there were no road signs whatsoever. Eventually, through some extraordinary stroke of luck that confounds me still, we drew up on a simple country lane lined with poplars and with a solitary building. This, my driver intimated unconvincingly, was the checkpoint. He then curiously got out and circumvented the van, suddenly opening my door to give me an unexpected inspection. Earlier, as we zig-zagged along poppy filled country, I had picked a red poppy and the flower lay on my seat: the driver deftly swiped it away just before Uzbek security guards walked upto me. Security checks in Uzbekistan were always nervous moments laced with the possibilities of cash depletion and unwarranted detention; video equipment and the lure of foreign currency had caused problems before. Though armed with letters of authority explaining our presence as "foreign experts", it could mean little in this remote location. The gruff guards demanded to see my "Exit Visa" (Exit Visa?), and repeatedly asked me if I possessed dollars or drugs. Hardly likely to say yes, I feigned an ambiguous answer for the former question and a decisive head waver, while I still had it, for the latter (thankful for the perceptive removal of the poppy!); we avoided the likely negotiations for a right of way off Uzbek soil after a small gift of tea. Across on Kyrgyz soil, our companion, Yaruslav, had waited patiently in his Russian jeep despite our delays. Rolling in Monet's Landscapes My entry into Kyrgyzstan was a flower strewn spectacle. On the little rural road that tapered ahead were gently undulating green hills devoid of trees or features. Blanketing these were lush green fields, flushed for kilometers with beautiful foot-deep velvety patchworks of wildflowers…millions of red poppies, yellow, white, lilac and mauve spring flowers and wild green grasses as far as the eyes could see. In an instant, the ghost of Monet seized my mind - what had he missed! This breathtaking meadow scenery (typical of Kyrgyzstan) made me stop the vehicle (we had a long way to go) and compulsively dive into this sea of flowers. Then we spread a blanket and gratefully shared Yaruslav's frugal lunch while gazing into this wild wonderland. It was a long, dark, bone-rattling journey. The country was devoid of all light and human habitations; towards midnight, exhausted, we drove into a forlorn concrete "engineers' guesthouse" in the windswept remains of an abandoned Soviet mining settlement. There was no sign of food - or activity - in this building (there were no other guests) which was unnerving until Yaruslav returned to led me to a "good place to eat".

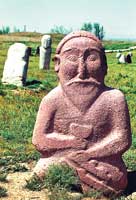

A short distance away at a village house, a few local souls had gathered together and, for once, the mere sight of others uplifted my spirits considerably. Whether it was pure hunger or just good taste I do not know (I suspect the latter), but there I dined unexpectedly on one (sadly one) delicious deep fried crispy Kyrgyz trout and bread - a meal which I have long remembered. When I awoke to my environment next morning, I realized with alarm that I had slept soundly at the foot of a towering mountain which had been bridged to contain a large dam full of water (and trout), poised several hundred metres above my head. Wild Horses and Gold-toothed Men of Toktogul Over the ensuing days, the jeep ambled through Kyrgyzstan: 94% mountain covered with an average elevation of 9000 feet, 30% of which is under permanent snow and glaciers. With 198,500 sq km of wilderness, it is home to only 4.5 m people: ethnic Kyrgyz (57%) - probably from Siberia, Slav (21% : Russian and Ukrainians), Uzbek (13%) and a 1% sprinkling of Germans sent here post World Wars. Formerly, though, the lands were overrun by a mix of ancient Scythian people (6C BC - 5C AD) and assorted Turkic tribes including the cultured Turkic Kharakhanids who introduced Islam in 6C AD, gradually eroding the Buddhist presence on the steppes. Genghis Khan dropped by in 13C AD and then left much of Kyrgyzstan as a gift to his son, Chaghatai. The going was hard but absorbing. The landscapes around western Kyrgyzstan and Toktogul are spectacular: panoramas spanned 200 degrees with unbroken snow-tipped mountains of the Kyrgyz-Alatau Ranges (and earlier Ferghana Range) forming formidable barriers. The dirt road through Ala-Bel, Otmek and Tor-Ashuu Passes we traversed could be seen winding its way far into the horizon. Intermittent plateaus were home to small herds of shaggy wild horses with suckling spring foals that roamed across frozen plains. In Tor-Ashu Pass (11,500 ft) we simply drove through a mountain via the longest tunnel I had encountered : the sheer cost of drilling it - for the odd vehicle that it served in this land of horses - seemed amazingly extravagant. In another snowy high pass, so cold that even the jeep was seizing, we stopped at the summit to warm up with hardened road workers who were living in steel containers. How they survived mid winter was beyond me, as spring was bad enough. Once inside, the warmth of their oil stove, in as much as the hearty Russian laughter by workers with numerous brazenly gold-filled teeth, a glorious gold version of Bond's dated "Jaws", was very welcome. When they realised I was from Sri Lanka, the workers immediately brought out "Dilmah Tea" to drink! We proceeded parallel to the Kazak border to Bishkek, the capital, now passing small villages that grew slightly bigger as we neared it. In this countryside, ancient donkey and horse drawn carts, not cars, were still the primary means of transport; the horses were stallions of considerable size, some cows equivalent to large prize-winning Danish stock - clearly the pasturelands were worthy of Genghis. Once I passed a huge stallion with two little village boys, under 6 years old, riding saddle-less. The lead boy held the reins while the next clung happily to him (and a bag of bread); however it was obvious that it was the mature horse that was in full charge of the boys, not vice versa. Bishkek Breakfasts Bishkek is intimately associated with my tongue over excellent Kyrgyz guesthouse breakfasts that surprisingly rivalled (possibly surpassed) that yardstick, The English Breakfast. With beautifully garnished radishes and vegetable platters, rich local cream and butter, yogurt drink, thick sweet syrupy fruit compotes, slices of various cheeses, assorted chewy breads and fried eggs, you were spoilt for choice: I had everything. The somewhat vacant capital was far less interesting than Tashkent but accommodated a pleasant (if run down) park and a reasonable museum. I attended a Russian Orthodox Church service one day with uplifting Gregorian-styled chanting and billowing incense, and watched the congregation's devotions from a balcony above, next to an antique organ. About 30 km from Bishkek lay the scenic Ala-Archa Canyons, a pleasant detour into pretty forest covered gorges with glaciers on the upper reaches and waterfalls lower down. Further on, about 80 kms from Bishkek and at the mouth of a picturesque Shamshin Valley, I visited Balasaghun, the ancient capital founded by Sogdian merchants (whose home was Afrasiab in Samarkand, see Part 2) and later conquered by the Kharakhanids. It was part of a chain of some 80 caravan towns that once existed in the region. Only a ridged mound of 10,000 square metres remains but, strategically placed on a sweeping valley corridor flanked by snowy mountains, a striking and solitary Burana Tower (11C AD, 83 feet tall) stands guard over the vista. Once it was even more awe-inspiringly 149 feet high (15 stories) but humbled by an earthquake. Adjacent, I wandered through a field of equally striking, rounded Balbal (ancient stone obelisk) grave stones, carved in a variety of bearded human forms, brought here by archaeologists for safekeeping. Buddhist temples of Kyrgyzstan Near Balasaghum, the settlement of Al-Beshim was home to two ancient Buddhist temples and a Nestorian Christian church (7-8C AD); in a dim corner of Bishkek's Museum of History, I had spotted archaeological drawings of what had lain here. On the site itself, I visited a tiny museum which displayed the distinctive Nestorian cross carved on large pebbles. (I had seen similar Christian symbols in the far Taklamakkan desert basin, including winged angels in Buddhist locations (Sunday Times Plus "Timeless Taklamakkan", February 5th 2006)). The earlier remains of four Buddha statutes were discovered here seated on high thrones in one temple, the many facets of life along these steppe lands of the Silk Road. Enchanting Lake Issy-Kul Issy-Kul ("Warm-Lake") is a fabled geographic and historical heartland for aeons. At 170 km long and 70 km wide and defined scenically by the rolling Tien-Shan range, it is the second largest alpine lake in the world, never freezing due to a volcanic under-bed. It was even deep enough at 700 metres to be the Soviet Union's secret torpedo testing site until the early 1990s (foreigners were banned here), tucked away in this remote corner of the earth. From here, with several ancient lake settlements, the ancient Silk Road passed through the formidable Tien-Shan, the backbone of Central Asia, through the Bedel (13,800 ft) and Torugut Passes to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan.

My plan - in distant Khiva - was to circumvent this beautiful lake and head south through the Torugut Pass into the Taklamakkan Basin. As luck would have it, all my attempts in Tashkent to obtain a pass through Torugut and a visa into Xinjiang failed (for now), both due to limited time and also the snow bound nature of southern Kyrgyzstan in May. Nonetheless, Issy-Kul afforded many pleasures while circumventing it. On its northern shores near Cholpan Ata, there lies an extraordinary boulder strewn glacial field. On south-facing boulder faces, Scythians (500BC - 1C AD) have etched detailed "rock photographs": figures with bows and arrows hunt Ibex flanked by either snow leopards or wolves. Some distance away, a more modern Communist Party had erected a sanatorium for its seniors. I stayed here, savouring the (rather sparse) facilities but with excellent views of the lake with its cold, clear, pebbled waters and Celestial Mountains that tower the southern shores; downstairs an old heated swimming pool offered a welcome wallow. Some exquisite dawns and pink-blushed evenings shadowed the sanatorium's gardens where former Party members had strolled while discussing the complex affairs of the Soviet Union. Further on, lakeside, my stay with a farming family rewarded me with some good home-cooked stews and last season's stored apples - a change from simple travelling rations. Near by in Karakol, a military-explorers' frontier town in the 20C, I visited a grand wooden Holy Trinity Cathedral (1895) and wandered through streets with Russian 'gingerbread houses' displaying gaily painted shutters and geraniums on window ledges. Later I gingerly tested a proud lean Kyrgyz race horse (very slowly) on a race track. About 25km from Karakol, the Jeti Oguz or "Seven Oxen" Canyon forms a sandstone spectacle: at its heart is Razbitoye Serdtse "Broken Heart", a blood-red coloured sandstone fault which, in popular lore, was a reference to a sabre cut through the heart in an ancient Kyrgyz fight between two warriors over a woman. Przhevalsky's Tomb I was determined to pay homage to the great Russian explorer, Nikolai Przhevalsky (1839-1888), whose remarkable wanderings and writings of flora and fauna from the Tibetan plateau to Siberia I knew of. He is best known for his discoveries of "Przhevalsky's Horse", "Przhevalsky's Gazelle" and the wild two-humped Bactrian camel; the former was (and is) the closest living wild relative of the modern domesticated horse and roamed Central Asia upto Mongolia, now thought to be extinct in the wild. Though locals had never seen this squat mule-looking horse, I later discovered live specimens (internationally bred in captivity) in the Dehiwala Zoo! Meanwhile, high on a cliff overlooking eastern Issy-Kul, a mausoleum commemorates Przhevalsky who died in Karakol (-then named immediately by the Tsar as Przhevalsk; his statue was later raised in St. Petersberg, one of only a handful of many illustrious Russian explorers to be afforded that fame). Blue-pine trees buffeted by Issy-Kul's winds shroud the mausoleum and a diminutive 80 year old white haired Russian lady custodian recited, straight off her memory, the most detailed and fluent account of Przhevalsky's life possible, answering my questions through Yaruslav. Gunfights on the Kazak Border Kyrgyzstan was a green soaring haven; many pleasant thoughts abound. The only estranged incident was confronted on the long arcing return from Bishkek via the vast southern steppes of Kazakhstan - a preferred shortcut to re-enacting the Ferghana experience by night. On our approach to a border point into Uzbekistan - how we found it I will never know - a gun battle raged in the darkness and sent us scuttling back into Kazakhstan. Meandering about in this vast countryside at night was no trivial thing, hungry, tired, confused and with limited petrol. Somehow, a different checkpoint was located and approached with much trepidation; we were then made to walk with our belongings across a barbed No Man's Land between two border posts, scrutinised by Kazak and Uzbek guards at either end. However, they were in a good mood and it was with no small relief that I found myself under the familiar street lights of gentle Tashkent. Reflections The sojourn in Timurid lands and its rich ethnic mix was one of the more interesting and illuminating experiences I had encountered on years of varied Silk Road journeys. The flavour of Central Asia is unique, despite all the more modern aspects imposed on it. Though the tragic legacy of Timur's carnage (frequently highlighted) cannot be overlooked and his 'greatness' cannot perhaps be compared with, for example, the internal wisdom of Emperor Asoka (who also began with bloodshed but ended with compassion), of his artistic legacy (into the Mogul period), trade and security of passage then, there is no doubt. It would do well for modern leaders to behold "Let he who doubts our power and munificence look upon our buildings" and try emulate something of Timur's greening skills exhibited in his beloved Samarkand, "the Garden of the Blessed". DNW: meridiana@sltnet.lk |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and the source. |

© Copyright

2007 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |