Business perspectives on free marketsThirty years after the liberalization of the Sri Lankan economy, there is mixed reaction and much debate from the business community on the accomplishments, the mistakes that have been made along the way and the sweeping changes that still have to be implemented in order to call it a true success. Sri Lanka has not only had to confront the challenges nations face when opening up their market but has had to deal with the problems in the context of a civil war.

Patrick Amarasinghe, a former Chairman of the Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry in Sri Lanka (FFCISL) said Sri Lanka rushed into a free market system a little too fast. "We went into an extreme end. In 1977, we should have liberalized the productive side," he said, explaining that raw material and machinery in the country as well as factories were not geared to international standards. Amarasinghe said a consequence from the rush to liberalize made Sri Lanka a dumping ground for inferior goods with no quality. Local industry also fell victim to the increasing profitability of importing cheap goods from places such as India and China where the cost of production is far less than in Sri Lanka . "Our local people found it difficult to compete," Amarasinghe said. The products coming into the country had lower standards and ruined local industry to a fair extent. "Importing was less cumbersome and cheaper and trade became more profitable." If not for the war, he believes Sri Lanka would have progressed much more. "If the war ends, things would be settled," he said. The country should also try and correct certain policies. Foreign investment is not coming in as expected but it is essential to ensure that existing local entrepreneurs will not collapse. "Lots of competition and labour is coming from India. We have a serious problem and labour shortages in every sector." He said government ministers must stop urging skilled locals to go overseas. In the context of regional development, Amarasinghe holds up India as having done it correctly. He also added that there is a greater feeling of nationalism in India as opposed to Sri Lanka. Former Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Chairman Chandra Jayaratne said the free market has succeeded in the global and regional context but the way it has been implemented and supported, in particular the policy framework development is not the right one. "There is contradictory policy and implementation and as long as you have such things, a free market doesn't succeed," he said. "You need a set of policy and guidelines for the long term and changes of regime are disruptive."

Jayaratne said possible gains from a free market have been hampered by a lack of political stability and political consensus on national policies that could advance Sri Lanka and its people. He said Sri Lanka should focus on infrastructure and a policy regime targeting comparative advantages in the region, especially capturing value from the Indian subcontinent in financial and service areas such as shipping, aviation, tourism and skills export. Undoubtedly, the ongoing conflict has affected Sri Lanka 's growth and development but Jayaratne said the war is not the only reason. "If we had war along with the right statesman running the country, good governance, justice and correct values in society, I think Sri Lanka would certainly have been a real financial and trading hub as well as tourism and in the movement of people such as aviation and ports." Jayaratne said local industry has not been as affected by the free market as shown and talked of by the private sector. As seen in India, a gradual opening of the economy accompanied by best practice and technology transfers would have helped local industries and even services areas to enhance competitiveness driven by comparative advantage. Jayaratne also said the private sector has not been responsive to liberalization. "Even though we asked for it, we don't like liberalization." He added that the private sector wants to make easy money on trading, are not good risk takers and have not implemented the changes that were requested to make the system work. FCCISL Chairman Nawaz Rajabdeen said the free trade agreements with India and Pakistan were initially met with skepticism and fear that Sri Lanka would becoming a dumping ground for their exports but in fact, Sri Lanka's exports to India have increased more than thirty fold. "With the free trade agreements, Sri Lanka has more to benefit than India." The same is true of Pakistan. Rajabdeen said expatriate remittances are sustaining the Sri Lankan economy. "With the current free trade agreements with India and Pakistan, we have some breathing room."

Industrial development is vital to Sri Lanka. Rajabdeen said the FCCISL is keen on sustainable, regional development as opposed to big time investment. "We don't want big time investments. We want to go to the districts like Anuradhapura, Batticaloa, Vavuniya and Hambatota." Rajabdeen also said that peace is hinged on development, particularly development in the North and East. "Northern and Eastern development is essential or the war will go on for the next three to four decades." Priority has not been given to cultivation. "We really have to address the agro base industry rather than giving subsidies to farmers for fertilizers. Then, I'm sure we will be ahead of other countries." Chairman of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Mahen Dayananda said despite Sri Lanka being the first country in the region to liberalize, it has clearly not succeeded to the extent it should have. The failure to resolve the ethnic conflict has retarded economic progress. He calls it a 'managed liberalization' because certain controls such as the capital account were not liberalized. Dayananda said corruption exists in most of the world and Sri Lanka is no exception. "Perhaps, post 1977 with liberalization and the unprecedented growth of the economy, the extent of corruption may have appeared to be of a higher order and far more obvious."

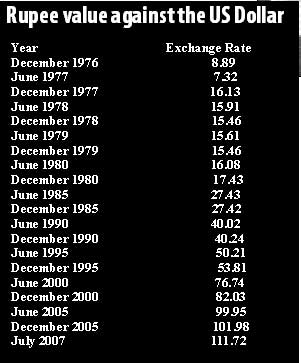

The local industry has had to make adjustments to the changes. Dayananda said there were several monopoly state corporations such as the Steel Corporation which had to adjust to market realities. Liberalization forced enterprises to change and adjust to the new global economic order. There was a degree of protection which Dayananda said continued to be extended to local industries, giving them much needed time to adjust to the new order. "It hurt inefficient industries, some of which were wiped out but overall, it created the urgency for change and adjustment which are positive." He warned against liberalizing blindly as there are several countries that preach liberalization but protect vital parts of their own economies, either directly or indirectly. K.C. Vignarajah, former Chairman of the Ceylon National Chamber of Industries (CNCI) said the results from opening up the market are mixed. "It was definitely a welcome move but the matter of operations initially and subsequently could have been handled much better." Initially, there wasn't sufficient time for readjustment of certain industries to make them competitive. In later years, there were too many macro economic factors which were within the control of the government but not attended to and the private sector suffered considerably. He said some local industries have been hurt through liberalization of the economy, mainly due to a lack of complementary policies. In the current context, exporters are undergoing grave hardships because of the macro economic factors. The inflation rate having touched 20%, interest rates ranging from 20 to 35%, the electricity rates, transportation costs, etc. being far higher than our competition, the infrastructure being woefully inadequate are factors beyond the control of exporters. He said unlike Sri Lanka any successful exporting country has a competitive rate of exchange to support the exporters. Various types of restrictions and licensing schemes only help racketeers and fuels corruption. Vignarajah said interference by the politicians was a sad feature that flowed out of the same government which also introduced the free market. "We have such a beautiful island with unparalleled talent for the size of this country. The sad feature is we have driven them away and are continuing to drive them away and not capitalizing on what we have. That is the tragedy." (NG)

|

|

||

| || Front

Page | News

| Editorial

| Columns

| Sports

| Plus

| Financial

Times | International

| Mirror

| TV

Times | Funday Times|| |

| |

Copyright

2007 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |