18th March 2001

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Plus|

Sports| Mirror Magazine

Comment

Are budgets a fiction?

The budgets of recent years have tended to be a mere presentation of figures that do not have much expectation of turning out to be correct.The expenditures overshoot the budgeted figures by considerable margins while the expected revenues do not materialize. Budget 2001 is not expected to be very different. Unfortunately the fictitious nature of the Budget figures is apparent even at the time of presentation owing to the unrealistic expectations. This is quite apart from unforeseen developments which may render the figures even more difficult to achieve.

Let us take the two aspects of revenue and expenditure separately and examine to what extent there is an element of realism in the budget figures. Revenue is expected to be Rs 265 billion. This is an increase of about 25 per cent from that recovered in 2000. This is a huge increase. The main increased tax revenues are expected from a surcharge in corporate taxes as a result of the surcharge of 20 per cent and an increase in the National Defence Levy by one per cent. There are other tax measures too but those cannot be expected to yield any substantial increases in tax revenues. When a tax rate is increased it yields higher revenue only if economic activity continues at the same pace or increases in momentum.

There is evidence that economic activities would be at a lower level this year and that the economic growth rate would drop to 4 per cent or less. In those circumstances the higher tax rates will not have the desired effect of increasing revenue by the large amount that the budget anticipates.

Further, one could question the wisdom in increasing tax rates on corporate profits at a time of expected recession in the economy, some of which are caused by the fiscal weaknesses themselves. For instance the higher interest rates as a result of the budget deficit would dampen expansion of activities as well as reduce profit margins of corporates.

Then how would the surcharge help? In fact most economists would argue that what was needed was a boost of economic activities through relief in taxation, which might help collection of revenues rather than increased taxation. But this was not to be. In these circumstances it is difficult to see how tax revenues will increase much.

The expected increases in tax revenue by as much as 25 per cent must be viewed in the context of 2000,when tax revenues were about 2 per cent of GDP less than expected for last year. This gives an indication of tax revenue trends. We have to believe that the collection of revenues would be more efficient this year. The mere computerization of the Inland Revenue Department is not likely to enhance tax collection efficiency.

When we turn to expenditures too there are reasons to believe that it is unlikely that expenditures would be contained within the budgeted levels.

Defence expenditure overruns have been the most conspicuous offending item.

The overruns have by no means been confined to these. Overruns in welfare expenditures and debt servicing costs have also contributed to the significant overruns in expenditures. Last year current expenditures were higher than the expected expenditures by 2 per cent of GDP.

It has also been the practice in most years to offset the overruns in current expenditures by curtailing capital expenditure. This happened last year by a very significant amount. The overall deficit is thereby contained to some extent. Last year's overall budget deficit is estimated at 9.8 per cent of GDP, compared to an estimated 7.6 per cent of GDP.

This increase in the overall deficit by 2.2 per cent of GDP was despite a curtailment in capital expenditure by 1.7 per cent of GDP. It is needless to say that such curtailment of capital expenditures is harmful to the long run growth of the economy. This year's overall budget deficit is expected to be 8.5 per cent of GDP.

This deficit is high. More important, will the government contain the deficit to this without curtailment of capital expenditure? It is most likely that even if the budget deficit is contained around this figure it would be achieved by a curtailment of capital expenditures.

It is most unlikely that the expected revenues would be collected by

the tax measures in place and new proposals. On the other hand, current

expenditures are likely to be much larger. Even if the budget deficit is

contained within the stipulated 8.5 per cent of GDP, this is most likely

at the expense of capital expenditure. In as far as economic growth is

concerned, the budget has no good news.

Bang bang budget

Militarisation of Sri Lanka's economy and Budget 2001

This is perhaps the first time in Sri Lan-ka a Chamber of Commerce is interested in looking at the social impact of the national budget. Amidst a shrinking Government and decaying State it is heartening to note that the business community is increasingly concerned about social effects of economic and fiscal policy. I welcome and thank the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce for engaging in such a public discourse on social implications of the budget in addition to economic implications. I propose to look at the social implications of the budget 2001 from two perspectives.

One is to look at the public expenditure on social sectors of the economy from 1997 to 2001, and compare with defence and total public expenditure.

Second is to look at some of the social implications of Government's fiscal measures enunciated in the budget speech by the Deputy Finance Minister.

Social Expenditures vis-a-vis Defence Expenditures

For our purpose, social sectors include Education and Higher Education, Health and Social Services, Samurdhi and Rehabilitation and Reconstruction.

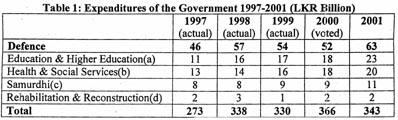

Table 1 provides the expenditure (both recurrent and capital) incurred for defence and social sectors from 1997 to 2001. All the figures are rounded up to the nearest billion.

Some of the social sector expenditures are coupled with some other sector/s. Since I could not get a breakdown of data, due to time constraint, I have made some assumptions. These assumptions would not alter the analyses.

The figures for 1997-1999 are actual expenditures, 2000 is voted expenditure, and the figures for 2001 is given in the Appropriations Bill presented to the Parliament.

According to Table 1, the defence expenditure has been greater than the combined total of social expenditures during each year under consideration (1997-2001).

Besides, we have to remember that the figure for year 2000 is only the voted expenditure. The actual defence expenditure during 2000 is undoubtedly much higher than the voted expenditure due to galloping military expenditures since mid-2000.

The government estimates that the defence expenditure during 2000 was in the region of LKR 82 billion (almost US $1 billion). The defence expenditure including deferred payments from last year is estimated at LKR 75 billion in 2001.

In this background, the allocation of LKR 63 billion for defence in 2001 in Table 1 is certainly an underestimation.

Generally, it has been the case during past several years that the actual expenditure on defence has been greater than the budgeted (voted) expenditure whilst the actual expenditures on most other sectors have been lower than the budgeted expenditures (see Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Annual Report, various years).

Therefore, I would argue that the defence allocations for 2000 and 2001 in Table 1 are under-estimations, while the allocations for social sectors are over-estimations.

Hence, the gap between the defence expenditure and combined social expenditure would be larger than what is apparent in Table 1. The defence expenditures have been rising during most years in the recent past, so were expenditures on Education, Health and Samurdhi though to a lesser extent.

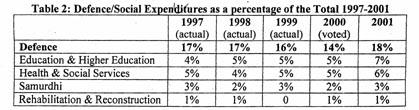

For purpose of comparison Table 2 is more relevant, which provides the shares of defence and various social expenditures out of the total public expenditure. Here again, the share of defence budget as a percentage of the total budget has been greater than the combined share of social sector budget during each year under consideration.

The government is commendable for slightly increasing the share of Education and Health budgets for 2001 (which have remained more or less static in the past four years) despite very tight fiscal position. However, whether the government can meet these targets is questionable, because in the past few years the actual expenditures on Education and Health have been considerably lower than the budgeted amounts.

The defence expenditure as a proportion to the total public expenditure (as well as in absolute terms) has been the second largest after the expenditure of the Ministry of Finance and Planning until year 2000. Public debt (domestic and external) repayments (amortisation plus interest) consume a large chunk of the expenditure of the Ministry of Finance and Planning.

However, in 2001 defence expenditure is set to overtake the expenditure of the Ministry of Finance and Planning for the first time in the fiscal history of Sri Lanka, thus becoming the largest single expenditure.

The allocation for defence in 2001 is LKR 63 billion, whereas the allocation for finance and planning is only LKR 46 billion. As a percentage of the total expenditure, defence is allocated 19% whereas finance and planning is allocated only 13%, pushing it to the second place. This is a disturbing development in the annals of fiscal sector of Sri Lanka. This is an indication of the changing nature of the State in Sri Lanka, which is fast becoming a militarised State.

The social implications of such a changing priority in fiscal policy are immense. There is a growing militarisation of the economy. The National Security Levy (NSL) is increased to 7.5%, and I wouldn't be surprised at all if it surpasses the Goods and Services Tax (GST) rate in a few years' time. There is more to defence expenditures than what is revealed in Table 1. This table shows only the direct defence expenditures.

There are indirect and hidden defence expenditures camouflaged under other allocations. Therefore, the actual defence expenditures would be much higher than the official statistics would want us to believe.

The rising defence expenditure not only eats into the public expenditure on the social sectors, but is also a main cause of social unrest throughout the country (directly and indirectly). The economic and social implications of the rapid rise in defence expenditure reverberate not only in the theatres of war but throughout the island.

It is widely acknowledged now, even among Government circles, that the primary reason for the upsurge in crime in southern parts of the country is the on-going civil war. The deserters from the security forces are the main culprits behind the crime wave sweeping non-theatres of war, while the main perpetrators of crime in the North and East are the armed Tamil paramilitaries who are aligned with the security forces (including robbery, kidnapping, and extortion from the business community). Moreover, the growing narcotic drug (especially heroin) addiction in the country since the early 1980s is largely a result of the civil war. These are some of the multiplier effects of rising defence expenditure that exacerbate the civil war.

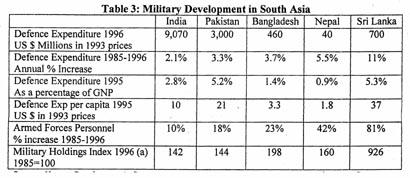

Further evidence of the militarisation of the economy and society in Sri Lanka is demonstrated in Table 3 by comparing defence expenditures of five largest South Asian countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka).

The defence expenditure of Sri Lanka in 1996 (US $700) is the third highest after India and Pakistan despite being the smallest country (in terms of physical and population size) among the five.

Sri Lanka had the highest annual percentage increase of defence expenditure in South Asia during 1985-1996 at 11%, which was double the rate of the second highest increase in Nepal. The defence expenditure, as a percentage of the GNP in 1995 was highest in Sri Lanka at 5.3%, just above Pakistan's 5.2%. Sri Lanka's defence expenditure per capita of US $37 in 1995 was the highest in the region while Pakistan trailing far behind at second place with US $21. Percentage increase of armed forces personnel during 1985-1996 was highest in Sri Lanka at 81%, nearly double that of Nepal (the second highest increase). The Military Holdings Index of Sri Lanka in 1996, which was 926 (taking 1985 = 100), is the highest in the region nearly fivefold that of the second highest of Bangladesh. These regional comparative data are up to 1996 only.

Since then, due to accelerating development of the defence sector in Sri Lanka, the gap between Sri Lanka and other South Asian countries may have widened.

These are additional statistical data that reaffirm the alarming rate of militarisation of the economy and society in Sri Lanka. This rapid development of the defence sector is nothing to gloat about.

Social Implications of Fiscal Measures

Now secondly, I would like to look at some of the social implications of the fiscal measures contained in the budget proposals.

On the positive side, the government should be congratulated for proposing to arrest the budget deficit from 9.8% of the GDP in 2000 to 8.5% in 2001.

If this proposed target can be attained it has the potential to lower interest rates and the rate of inflation from the current high levels. However, I have to emphasise that this is a big if.

Besides, the potential reduction in the inflation rate due to a reduction in the budget deficit as a percentage of the GDP would be more than offset by additional revenue raising mechanisms outlined in the budget.

The increase in scholarships for students in the education sector, introduction of a free health insurance scheme for public sector employees, series of incentives for Sri Lankan expatriate workers, establishment of a National Enterprise Development Bank, and several incentives to the handloom and handicraft industry are welcome steps by the government at this critical juncture. A series of incentives offered to Sri Lankan expatriate workers would economically and socially enhance the livelihood of hundreds of thousands of rural households.

The proposed National Enterprise Development Bank is intended to cater the needs of small and medium enterprises, which would enhance the economic and social wellbeing of those enterprises that are spread throughout the country. Several incentives and enabling environment extended to handloom, powerloom and handicraft industry would have economic and social benefits to the rural hinterland.

On the negative side, increases in utility charges (electricity and water) and surcharge on import duties prior to the budget, and surcharge on corporate profits, rise in the NSL and imposition of GST on private health services at the budget are bound to accelerate the rise in cost of living during this fiscal year, and perhaps even beyond.

Surcharge: a new euphemism in the past few months, 'surcharge' is being used in the fiscal lexicon at a high frequency in Sri Lanka. Firstly, the Ceylon Electricity Board introduced a 25% surcharge on electricity bills from March 2001 for one year.

Secondly, there was a 40% surcharge on import duties since February 2001 until the end of this year. Thirdly, a 20% surcharge on corporate tax is imposed for one year from April, according to the Budget Speech. We are told that these surcharges are only temporary increases in tariff/tax rates, and therefore it is so called.

Undoubtedly these surcharges would be passed on to the consumers, which will increase the cost of living further. Already, due to increasing military expenditures and oil and gas price hikes in the past year, the inflation rate has increased to 10% by the end of last year.

The imposition of several surcharges and a 1% rise in the NSL would exacerbate the rise in cost of living during 2001. The inflation rate is expected to top at least 12% by end of this year.

The government may act in good faith as regards these temporary austerity measures. Even if the Government rescinds these temporary surcharges at a later date it is highly unlikely that the prices of non-agricultural goods and services would drop.

The consumers are well aware that prices of non-agricultural goods and services hardly come down in Sri Lanka. Most of the times there is only one direction the prices know of.

Further, there seems to be some muddle in fiscal policy making. The current account deficit of the balance of payments soared to 7.4% of the GDP in 2000 from 3.8% in 1999, resulting in an overall deficit of US $516 million in 2000 compared to US $263 million in 1999. The free float of the rupee in January 2001 seemed to be intending to mitigate this precarious balance of payments position.

However, the subsequent 40% surcharge on import duties would partly nullify the positive effects of the free float of rupee on the balance of payments. This high surcharge on import duties is a roll back of the process of liberalisation of the international trade sector since the late 1970s. Likewise, while the introduction of a free health insurance scheme to public sector employees seems to be a positive development in the reform of the public health sector, the imposition of GST on private health services would at least partly negate such positive development.

Rapidly rising cost of living is expected to intensify labour unrest in the country through demands for wage/salary increases from marginalised income groups such as the plantation workers in the hill country, and lower rungs of the public and private sectors. The present campaign of the plantation workers for a pay rise is already leading to an economic and social catastrophe in one of the largest net foreign exchange earning sectors. If the present campaign persists, then it would exacerbate the already volatile balance of payments position of the country. The acceleration of cost of living is bound to further disturb the social peace throughout the country.

Further, the government may be forced to borrow from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to tide over the anticipated budget deficit and the deficit in the current account of the balance of payments. These loans may be extended with stringent conditions of economic reforms, which may exacerbate labour unrest. The social and political stability would be eroded if the financial burden of civil war has heaped on the ordinary masses.

Disappointingly, there is no new strategies outlined towards poverty alleviation.

This cynicism is further compounded by the Government's claim that only 16% of the population live under the poverty line, whereas almost 50% of the population receive a monthly cash allowance through the Samurdhi programme.

On the contrary, the Poverty Framework presented by the government of Sri Lanka at the last Development Forum in Paris reveals that over 30% of the population live under the official poverty line (which is more realistic to me). This vastly different data seems to be an indication of the slipshod manner in which the government addresses the issue of poverty.

In conclusion, overall the National Budget 2001 is more of a military developmental budget than economic and social developmental budget. The Appropriations Bill for 2001 presented to the Parliament reveals that the allocation for defence is the single largest. In year 2000 also the defence expenditure may have been the single largest. We don't know yet, but the difference is that the massive defence expenditure incurred during 2000 was not planned for. Whereas in the budget 2001 it is consciously planned for.

The major thrust of my evaluation of the national budget 2001 is that the marginalisation of social expenditures vis-a-vis the defence expenditure, and the social impact of the austerity measures largely stems from the protracted civil war (directly and indirectly). We only hope that the current peace process bears fruit and that the galloping defence expenditures and the associated economic and social after-effects can be at least partially rolled back in the near future.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to